Introduction

The corpse flower, also known as a titan arum (Amorphophallus titanum) is a plant that is native to Sumatra, Indonesia. It is sometimes incorrectly called the world’s largest flower, but it is actually the largest unbranched inflorescence in the world. As well as having a spectacular bloom, the corpse flower has a fascinating life cycle. It also has a rather fun botanical name because Amorphophallus titanum is Latin for giant misshapen penis.

Every year, the plant starts off from a several month period of dormancy existing only in its corm beneath the soil. The corm is a swollen underground plant stem where the plant stores its energy. It is made from solid tissue and can get quite heavy. The corpse flower has the world’s largest known corm, and the corm is typically about 100 lbs (50 kg). Considering the energy that must be stored in the corm to produce the large blossom, it makes sense that the corpse flower would have the world’s largest corm.

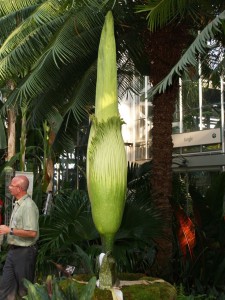

After the period of dormancy, the plant develops either a single leaf or a blossom. It produces a bud that emerges from beneath the soil that can be seen in the below photo. [I took this photo at University of North Carolina at Charlotte’s Botanical Garden.] When the bud emerges, there is no way to determine if it is going to be a leaf or a blossom. It is only once the bud gets tall enough and enough of the green sheaths (sort of like leaves but they are not) have fallen away that it can be determined if it will be a blossom or a leaf.

The Bloom Stage

The corpse flower does not bloom on a regular cycle. The ones in cultivation can go several years or decades between blooms. In the wild, they tend to bloom much more frequently. When they do bloom, it is spectacular. The bloom structure consists of a spadix, the inner central tube structure that is surrounded by a spathe. The spathe is the singular petal-like structure that is initially tightly wrapped around the spadix until it blooms, when the spathe open into a vase shape. The spathe is chartreuse on the outside, and when it opens, its deep crimson interior color is revealed. The spathe and spadix structure is what is sometimes mistakenly called a flower. The spathe actually protects the real flowers of the corpse flower. The real flowers are hidden at the bottom of the spadix and the reason for the famous smell of the corpse flower.

Corpse flower before opening. The spadix is the inner yellow-green structure. The pale green spathe envelopes the spadix and has a fringy top. Dark green sheathes surround and are falling away from the spathe.

A corpse flower in peak bloom. The spathe has opened in a vase-like structure that circles the spadix.

The corpse flower has both male and female flowers. The female flowers form a ring at the bottom of the spadix, and the male flowers form a ring around the spadix just above the female flowers. When the spathe opens, the female flowers are ready to be pollinated. The plant releases its famous rotting flesh odor to attract pollinators such as carrion beetles and flesh flies who like that sort of thing. The spadix heats up, reportedly close to human body temperature, to help volatilize the smell and carry it far away and bring more pollinators. The pollinators enter the vase like structure looking for flesh to eat, and surprise, they were tricked by the plant. They crawl around the bottom of the spathe and unintentionally pollinate the female flowers with pollen they picked up from other corpse flower plants. The plant has even more tricks up its sleeve, er spathe, though. The spathe only stays open for about 24 hours, so pollinators that can fly out can leave, but pollinators that either can’t fly or were too slow get stuck in the plant as the spathe closes. The reason for this deviousness is that the male flowers don’t bloom until a few days after the female flowers. This prevents the plant from self pollinating and increases genetic diversity. The pollinators are thus stuck in the plant for a few days until the male flowers bloom, and the spadix then collapses. At this point, all the stuck pollinators have picked up pollen from the male flowers and can escape out when the plant falls over. Pretty darn clever in my opinion.

Female flowers three days after the peak bloom date for this corpse flower. A hole was cut in the base of the spathe to reveal them.

The male flowers form a ring around the base of the spadix above the ring of female flowers. A hole was cut in the base of the spathe to allow harvest of the pollen. The hollow area between the spathe and spadix at the base of the plant can be seen.

An interesting note about the blooming process is that these plants are notoriously fickle and unpredictable. Sometimes the spathe opens much slower than the horticulturists would predict. Sometimes the entire structure collapses before the spathe ever opens. In 2010, a corpse flower was ready to bloom at the Houston Museum of Natural Science (HMNS). This particular corpse flower was taking far too long to open, and the staff was worried it might collapse before opening. Therefore they cut a small hole at the base of the spathe, and they injected a small amount of ethene gas into it. Ethene is a naturally occurring gas that is produced by some fruits such as apples as they ripen and also produced by some plants when they are injured causing them to die. Ethene is also used commercially to ripen some fruits such as bananas and tomatoes that are harvested before they are ripe. In the case of HMNS’s corpse flower, the ethene gas helped the plant to finish the blooming process, and it opened a few days after the ethene injection.

US Botanical Garden’s Corpse Flower

In July 2013, a corpse flower bloomed at United States Botanical Garden (USBG) in Washington, DC. As soon as I found out about it, I visited it daily to take photos. This is a compilation of some of the photos I took. Lots and lots more photos can be seen on my daily posts: July 11, July 12, July 13, July 14, July 15, July 16, July 17, July 18, July 19, July 20, July 21, July 22 (peak bloom), July 23, July 24, and July 25. To better display how the corpse flower changed while I was photographing it, I have assembled some of the photos that show the entire plant on this page to make it easier compare them. To view more zoomed in photos that show some of the details of this beautiful plant, please see the daily posts linked above. [Also, clicking on any of the below photos will open up a larger version of the photo.] Also below is a slideshow of my photographs that shows the progression of the blooming process.

July 11

July 12

July 13

July 14

July 15

July 16

July 17

July 18

July 19

July 20

July 21

July 22

July 23

July 24

July 25

The Blooming Process

This is compilation of my daily photos to allow better viewing of the plant’s changes. It also has several up close photos of the plant to show the beautiful details of it.

The Leaf Stage

In most years, the corpse flower is not producing a blossom and instead produces a leaf. In the leaf stage, the plant can produce energy and store it in the corm to use in years when it blooms. The US Botanical Garden also has on display a corpse flower in the leaf stage. Below are photographs of it. This is considered to be one leaf. The leaf just happens to be about four feet tall or so. I don’t know the exact height, but I had to squat a little underneath the canopy to get the last photo. One of the things I love about the particular plant is the white spots that randomly decorate it. The white spots can be seen on the leaf’s “stem”. It can also be seen on the outside of the blossom’s spathe and its sheaths.

References

I am not an expert on the magnificent plant. I am just obsessed with it. All the information on this page I found through various sources on the internet and from asking questions of the US Botanical Garden staff. For more information, below are some of the sources I found most helpful.

Pingback: USBG Corpse Flower: July 18 | Geeky Girl Engineer

Pingback: USBG Corpse Flower: July 19 | Geeky Girl Engineer

Pingback: USBG Corpse Flower: July 17 | Geeky Girl Engineer

Pingback: USBG Corpse Flower: July 22 am | Geeky Girl Engineer

A magnificent obsession and beautifully done. Thanks for putting this together.

Hello geeky girl. I’ve been reading your blog and I think what you’ve done is lovely. It was really interesting to see the process of the flower blooming. I hope to one day be a chemical engineer just like you and study biological systems like this one!

this is cool

Pingback: Conversations I have with my Mom | Geeky Girl Engineer

Thank you!! This was most helpful! We have one on display at Lauritzen Botanical Gardens in Omaha, NE, and I was trying to figure out how much time I had to see it until it blooms!!

Good luck!