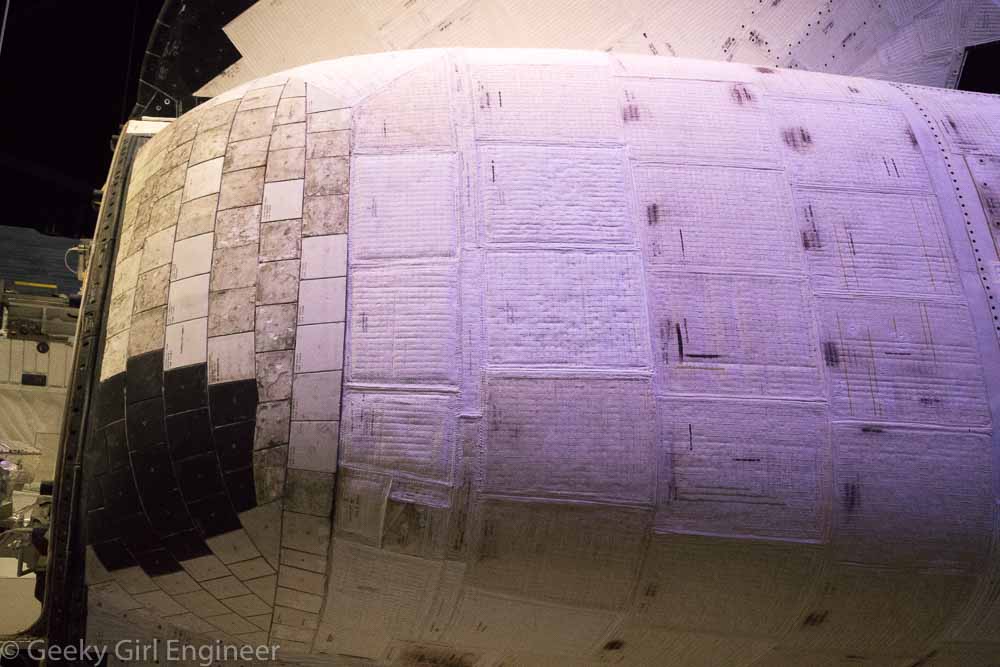

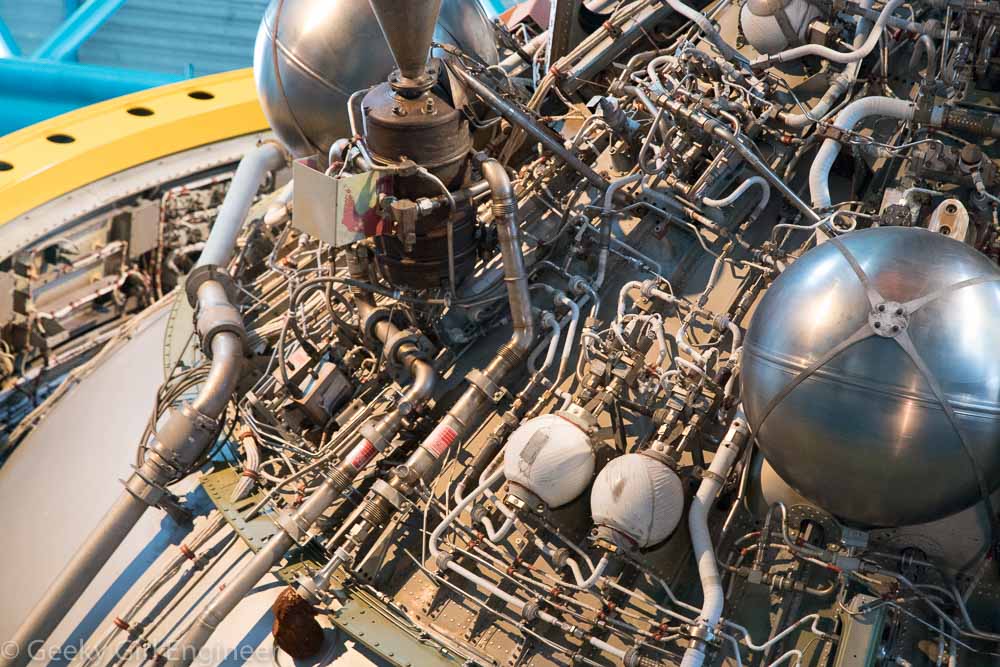

Today was my first visit to the Cape Canaveral area and to the Kennedy Space Center. The big exhibit here is the space shuttle Atlantis. They have it set up really nice, so you can see inside the payload and the damaged external heat shield tiles and blankets. There are plenty of other exhibits to see. Also, you can also take a bus ride to another site to see a Saturn V rocket. The rocket is impressive, and the bus ride is a very short tour of the center and worth the ride.

Category Archives: Science

Jamestown Artifacts

My tour of Jamestown included a behind the scenes tour of the vault, where they keep many of the archeological finds and the laboratory where they process the finds. In the lab, our guide showed us how where they clean and dry the samples. She also explained how all the finds are identified and coded. My favorite part was her describing how they identify, collect, and store all artifacts found at the site, including potato chip bags, CDs, and USB drives. I suppose technically CDs are becoming historical objects.

The vault contains wonderful artifacts, and they are very clear to explain that the artifacts all represent historical trash. Essentially everything they have was found in a historical Jamestown trash hole. Many of the trash holes were water wells that became contaminated with salt water, so they just threw their trash in it for archeologists to dig up and treasure hundreds of years later. [Consider that next time you litter.] They have collected lots of bones from various wild and domesticated animals, pottery, glass, and metal objects. They have many old building material artifacts also. The collection is just amazing. What is even more amazing is what people throw away. Some things never change.

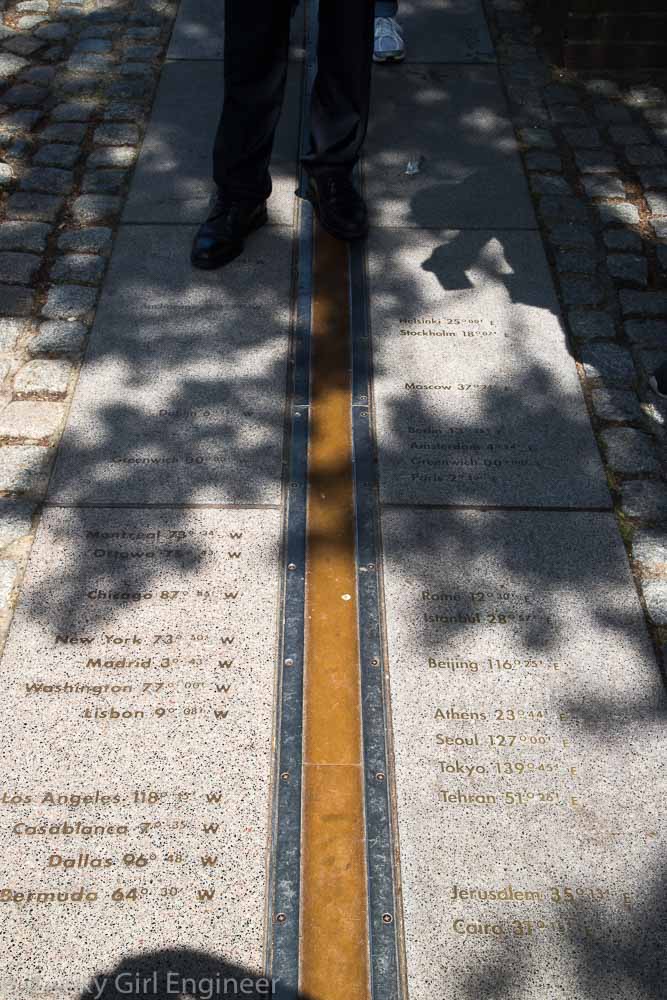

Royal Observatory

As I am an engineering geek, I felt that one of my must see stops on my London trip was to Greenwich to see the Royal Observatory. I think many people go just to take a photo of themselves on the Prime Meridian. That is a draw, even for me, and it clearly was popular based on how difficult it is to actually have a moment to take a photo on it without tens of other people in your photo frame. The observatory has some really good exhibits both about the history of the actual observatory and also timekeeping in general. It explains how it was first important for sailing and navigation. It is educational, and the displays of old timekeeping devices and navigation astronomy tools is fascinating. Also, the observatory is up on a hill and offers outstanding views of the area.

More on Kilograms Are Not Weight

I just finished reading Randall Munroe’s book “What If?” It is a fantastic book. The book is mainly (completely?) a collection of posts from his website xkcd.com, which is a great comic strip. The book is funny and rather educational as it contains scientific answers to absurd questions.

However I have bone to pick with Mr. Munroe, or perhaps I would simply like him to explain just what the heck he is talking about in the chapter and post “Expanding Earth.” The question regards weight gain people would notice if the Earth started to expand. He explains how gravity would increase, so your weight would increase. No arguments from me. I agree. However the part where he completely loses me is that not only does he not distinguish between mass and weight, but he refers to a person gaining mass, not gaining weight, and using units of kilograms. I don’t know what this means. To quote one part of the post, “After five years, gravity would be 25% stronger. If you weighed 70 kg when the expansion started, you’d weigh 88 kg now.” No, Mr. Munroe, I hate to contradict you, but you most certainly would not. You could certainly gain mass, in which case you would weigh more. The increased gravity would cause you to weigh more independent of if you had or had not gained mass. However the simple increase in gravity would not cause you to gain mass, but it would cause you to gain weight.

I blogged before about my annoyance with people who use kilograms and refer to it representing body weight. Kilograms is a unit of mass, not force. A weight is a specific type of force due to the acceleration of gravity being applied to a mass. If you are comparing or discussing some mass on Earth, then you can refer to them in kilograms and ignore the weight because gravity is constant. [Gravity is not in fact constant across the planet. It varies a little due a couple of factors, mainly latitude and altitude, but I am trying not to get too technical.] For example, you could say the average American has a body mass of 80 kg, but person X has a body mass of 65 kg. People will commonly say the average American has a body weight of 80 kg. They are wrong, but at least all of this is being said with a constant gravity.

In the “Expanding Earth” post, he continues to use the units of kilograms, even though he is clearly referring to weight increasing due to the acceleration of gravity increasing. If he had used Newtons for units of weight, the post would make sense. Quite frankly, in the post I don’t know why he didn’t discuss this to begin with. However, I can’t understand what 88 kg means in the situation he describes. Is he increasing the force of gravity to the weight but then removing the standard gravity to relate it back to a mass? Why would you do that? Is he using a ratio of acceleration due to gravity to apply to the mass instead of properly applying it to the weight? How is this less confusing? I am confident he knows the difference between mass and weight. Did he really not think people would understand his answer if he used proper units? Does he actually mean that your mass would increase? Would the mass increase because you can’t move around due to the increased gravity?

I know I sound really nit picky, but what hope do the scientific literate have of getting people who don’t understand the difference to understand the difference, if a physicist doesn’t use proper units?

Wind Cave National Park

This morning I visited Wind Cave National Park. On the surface, the park looks like much of same lovely grassland as the surrounding area. Underground, however, lies a huge cave system filled with gorgeous formations. The cave is famous for its boxwork formations and has most of the known boxwork in the world. You can take tours of a small portion of the cave, enough to get a glimpse of the gorgeous boxwork.

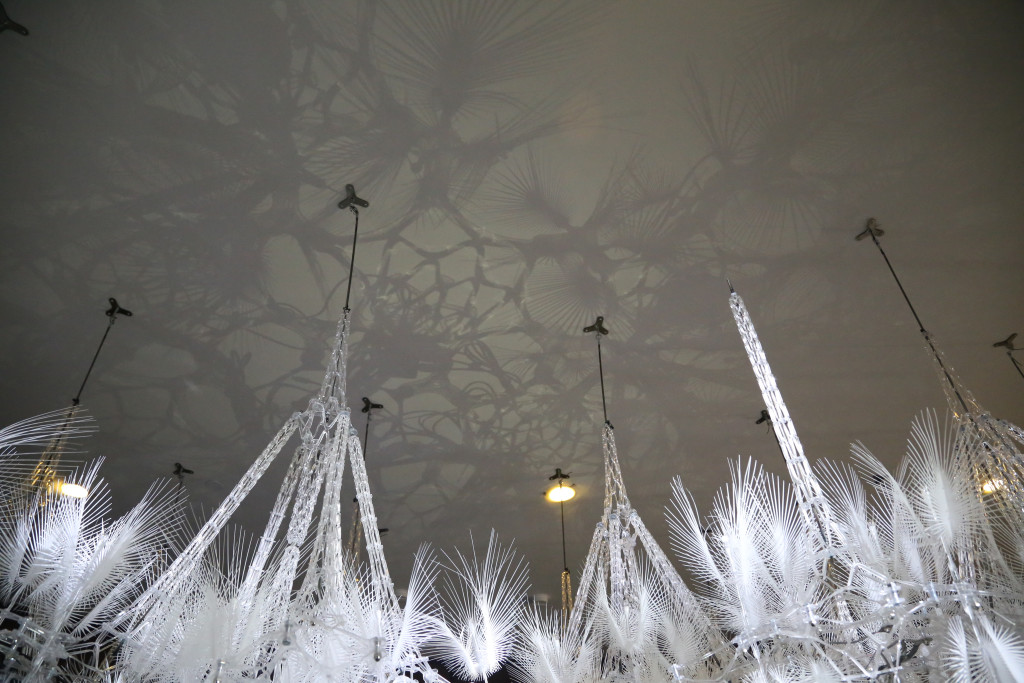

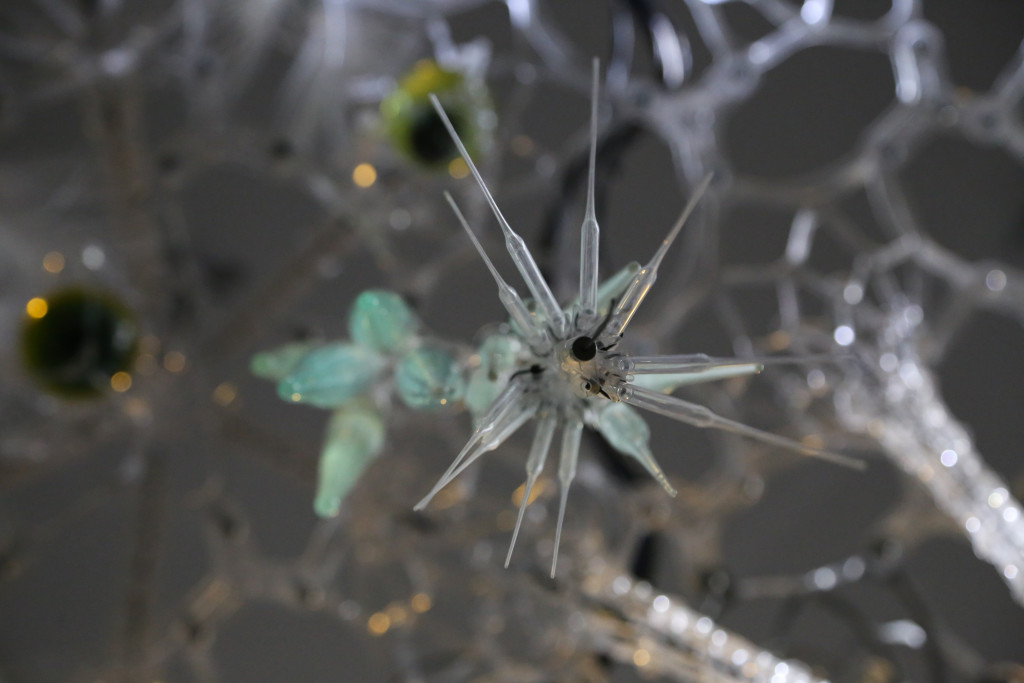

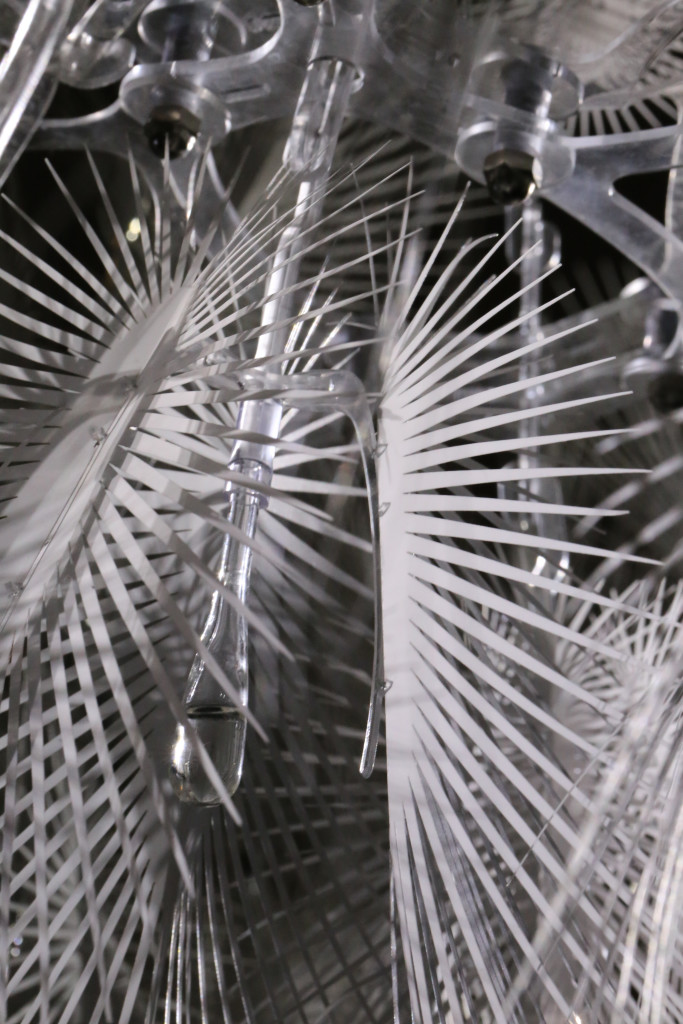

Sentient Chamber

There is an art exhibit at the National Academy of Sciences called Sentient Chamber that is unlike anything I have seen before. It reminds me of a gigantic hairy caterpillar. It kind of looks like technology and science based items hung as a chandelier among other items I associate more wind chimes. It is interactive because as people get close and walk through it, lights turn on, sounds are made, and certain items move or vibrate. I really can’t describe, but it is beautiful and interesting to look at. It makes really cool shadows on the ceiling, walls, and on itself. It also makes some really cool reflections in itself.

Communicating with Peers and the Public

I’m at a scientific conference currently. All day yesterday, I was in the same room listening to presentations on the same topic, mainly from people doing pure research, with some people doing research with more application objectives. At the end of the day, they brought several of the presenters together for a panel discussion. I had listened all day to many of the presentations, and I was growing somewhat concerned about the implications of some of the research. I support their research. I respect their research. I want to see more of their research. However I do not work in research, and where I work, communicating with the public can be very important. So I asked members of this panel a question. How are they going to explain to the public what they are doing. There is nothing unethical about what they are doing. They are doing good work that could lead to important information being revealed, but they are doing research in the real world, that quite frankly is not at this point meant for the real world. So I wanted to know, had they thought about how to explain the results of their research to the public? A member of the public who saw some of their data could become seriously confused and scared because they wouldn’t understand what the results mean.

I generally am not all that good at communicating. I am fine with public speaking if I have a script. However in public or even one on one, when speaking impromptu I many times stumble over my words. I sometimes have trouble getting all the thoughts in my brain to come out my mouth in a linear manner. I know it is a fault. I work on it. I have also been told by people that I sometimes talk at too high a technical level. I work on it.

So there I was at a scientific conference trying to ask people, many of whom I had known for a day or two, a question. I respect these people and their work. I am trying to ask a question and explain that members of the public might not understand their results. The irony is beyond rich. I, who have trouble communicating at times, who have trouble communicating at a level that others understands technical information, am trying to explain to my peers that they are doing work in a situation that members of the public can see their work, and members of the public will not understand their work.

Of course I stumble on my words. Of course I can’t explain myself clearly. And of course, these scientists I respect start getting defensive. They explain I don’t understand what they are doing. They try to explain what they are doing as if I have not already seen several presentations explaining what they are doing. One interrupts me before I can fully try to explain what I am saying. I explain I completely understand what they are doing, but members of the public won’t. I only want to know how they will explain their results to the public. I don’t want to argue with these people. I hate arguing. I just want them to understand my point of view. I stumble trying to explain. My heart starts racing so badly that I am shaking. I try to calm myself and explain differently what I am saying. A couple of people finally start to understand what I am asking. One responds “oh well, we will explain [jibberish].” I thought I had trouble communicating. No one would understand that.

A woman I have started to have a professional relationship with and have started to become friends with also was sitting next to me. Afterwards, she assured me she completely understood and had the same concern. Then several other people, who are not doing this research, came up to me and said they understood and shared my concerns. I thanked them for that. They have no idea how much I needed that. I hate arguing with people. I don’t want these researchers to think I don’t support their work. I want these people to like me, and I know we share a common goal.

I live and work by a couple of rules. I will not lie to people, and I will not put people in danger. Those are at the top of my list of rules. Telling people the truth is easier said than done when the truth involves highly complex information. It is difficult to explain what the results mean to the public when you don’t understand what the results mean. I work with some awesome people, some of whom take what I write and translate it so a normal person can understand it. I make sure it is technically accurate, and they make sure people can understand it. I understand the importance of communication. You have to tell people the truth, but you have to tell people the truth in way they can understand it. When you don’t understand what your truth means, you also have to tell people that truth.

It’s Not Rocket Science

I subscribe to my county’s weekly police report just in case there might be crime in my area I want to know about. I don’t live in a high crime area, so normally the police report is a bunch of car break-ins and drunks in the bar area of town. Today though I found this interesting report.

“MISSILE INTO AN OCCUPIED DWELLING, [location of incident]. On January 18 at approximately 6:51 p.m., a resident reported a known suspect threw a brick and rock into her residence, shattering two windows. [Suspect name] was arrested and charged with missile into an occupied dwelling, destruction of property, drunk in public and violation of protection order.”

What I found interesting is that legally speaking, a brick and/or a rock is considered a missile. To me this is another reason why rocket science should not be the go to science and engineering field for things that are hard. I hate the phrase “it’s not rocket science” with a passion. Rocket science is not that hard. It involves controlled combustion and trajectory. Missiles, a term which is generally used to mean a rocket that will cause destruction, is quite frankly easy. Science fields that are hard involve things that can’t be controlled near as easy as rockets, like biological systems, like fields trying to predict what stupid humans will do, like basic science where we are still trying to understand all the forces involved. You try doing an environmental and human health risk assessment on a hazardous waste site where toxicologists are unsure what level of exposure to a contaminant is acceptable, where you can’t be completely sure what humans will really be doing and for how long at a site, where people want to know they will be not be subject to undue risk for the next 70 years, and where you can’t be absolutely, completely positive just how much of each contaminant is there, but the polluters don’t want to clean up more than necessary. Then come talk to me about how hard rocket science is.

In summary, as evidenced by this police report, missiles are easy. Rockets are easy. Stop comparing things you think are hard to rocket science.

No, I won’t #HackAHairDryer

Evidently, IBM wants to encourage women to enter science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) by telling them to hack a hair dryer. My first thought is that while I appreciate any technology company encouraging women into STEM, did they really have to pick a hair dryer? I would like to give them the benefit of the doubt that it’s a cheap piece of electronics, but let’s be real. By picking a hair dryer, they are reinforcing stereotypes about women and how we care about our looks. I initially thought I don’t even own a hair dryer, then I realized I may own two. I know there is one in my guest bathroom, left by a relative, and it sits there in case any guest wants to use it. I may have one of my own in my bathroom, bought over a decade, possibly two decades ago. I am not even sure if I still have it because it has been a decade at least since I have used it.

My second thought about #HackAHairDryer is, YOU’RE A FREAKING COMPUTER COMPANY! ENCOURAGE WOMEN TO WRITE CODE OR HACK A COMPUTER IN SOME WAY! Computer science is one of the most underrepresented fields, even among STEM fields, it is one of the worst. For goodness sakes IBM, you are a computer company, encourage women into computers. That is a field you should know rather well. Surely you can think of things women can hack in your own field, things that will not play into stereotypes.

My third thought is what age is this campaign aimed at? Hair dryers use electricity, and they produce heat. They are not exactly the safest things to hack. In IBM’s video, there are a few scenarios for “hacked” hair dryers that quite frankly worry me a bit. If a girl or women wants to hack a hair dryer, great, but I hope there is someone (man or women) around who would know when they are getting into dangerous territory.

I can MacGyver with the best of them. In truth, a whole lot of my hacking knowledge did not come from school. It came from playing with things, looking things up on the Internet, and talking with other people with experience. I don’t “hack” that much. I do have a propensity to take things apart just to look inside and see how they work, which is easy. The difficult part is getting them back together again and having the thing still work as intended.

A final thought I have is aimed at any inspiring engineer. If you don’t like to hack, if you have never hacked anything, my personal opinion is that this means nothing to your aspirations to be an engineer or scientist. Don’t let anyone tell you, you can’t be an engineer or scientist because X. I can’t remember hacking a single thing before college. I can’t remember hacking a single thing as part of my undergraduate or graduate school experience. My education did involve some hands on stuff and science labs, but it did not involve hacking. Most of engineering education is theory and reality of design. That is, first you are taught the theory as to how something should work. Then you are taught how it doesn’t always work like the theory, so here are some empirical equations with fudge factors that do work. Now throw in some safety factors. Ta la, you have your design.

So young women, hack if you want to, whatever it is you want to hack. Explore the world. Stay curious. Learn how things work. Learn ALL subjects and find the ones that interest you the most, no matter what they are.

IBM, back off the hashtags. Do something actually meaningful that will encourage women into STEM like sponsoring science fairs or building competitions or sponsoring college scholarships.

Science, the Media, Graphics, and Communication

Recently, I had my annual performance review at work, and one of the things my boss said I needed to work on was communication with upper management in the form of not realizing they don’t know what I think everyone knows. I fully admit that there are some things so engrained in me that it would never dawn on me that other people do not actually know those things. Perhaps it is a reaction to the fact that I HATE being talked down to. I hate when people attempt to explain something to me I already know. The more basic the fact the more I hate it. It feels insulting. I hope those people where I have to go back and explain at a lower level, take it as a compliment, as it kind of is. I sometimes assume they already know things, and while I will correct it when necessary, it really is a compliment that I assume someone knows something they don’t. However, I do understand what my boss was saying, and science communication is something a lot of scientists talk about a lot. How can scientists improve science communication so that non-scientists can understand science, especially since science concepts sometimes are complicated?

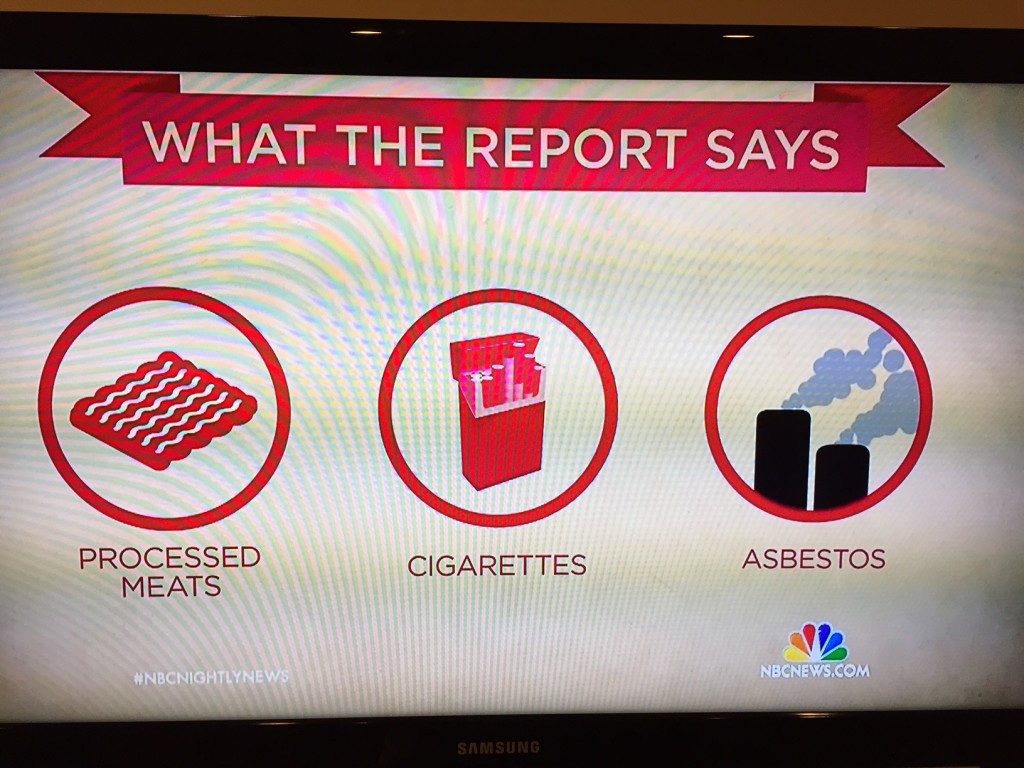

So in one of those striking coincidences, the same day I have my performance review, the World Health Organization (WHO) comes out with a report that says that processed meat is carcinogenic to humans. The blog post is not meant to go into a discussion of how badly this report was blown out of proportion by much of the media. I will just say there is a difference between relative risk and absolute risk. This Forbes article I think does a pretty good job of explaining what the WHO said and also what it means, and this post by Cancer Research UK is really good and has wonderful graphics explaining risk. I will also say I am not a vegetarian, and although I really don’t eat that much red meat or processed meat, I don’t have a thing about bacon, but I spent a good part of childhood in Texas, and God bless Texas barbecue, meaning brisket so tender no knife is needed, and now I am hungry. I’m sorry where was I? Oh right, WHO and processed meat. So what I did want to say a few words about was a graphic I saw on NBC Nightly News, mainly the image below (which in case it is not obvious, I literally took a photo of my television screen).

I am not an expert on asbestos, but I can say with confidence that a smokestack is NOT where asbestos originates. Asbestos is a naturally formed mineral, and in some locations, you can be exposed to asbestos from the natural soil and rock near you. Where people generally get asbestos exposure is old house insulation, old pipe insulation, car brake pads, and a whole lot of old building material. I posted this photo on Facebook yesterday because I was just kind of flabbergasted. It leads me to questions like does NBC News seriously not know where asbestos comes from? Are they just too lazy to find a better graphic? One Facebook friend said that maybe they used a smokestack to designate a generic industrial process. I replied that by that analogy cigarettes should also have a smokestack because they also come an industrial process. Asbestos does not originate from an industrial process. It originates from the earth, but it was then used by industry into various products. The other two graphics imply where your exposure to the named carcinogen would be. Your exposure to asbestos is not from a smokestack. It is from old building material like insulation. They could have had a graphic of fibrous pipe insulation. They could have also just had a graphic of fibers to show what asbestos looks like under a microscope. I feel confident that with a short period of time and a graphic designer, we could have come up with a factually correct and simple asbestos graphic. One may very well already exist. This reply led to a bit of a discussion between my friend and I that was partially about science communication. In short he said that because my reply was so long explaining the problems with the graphic, that he stood by his opinion that the graphic was fine. I acknowledge that my reply was long, but I was not wrong on any points. Also the NBC graphic was just plain bad. A smokestack does not in any way represent asbestos. Worse than that it provides incorrect information to an uninformed viewer who might think that a smokestack is in fact where asbestos exposure comes from.

I very much respect the points my friend made, and he did state something that gets at the heart of a problem I often have, which is brevity. [How long is this blog post now?] I have a tendency to give long answers, which I understand can be annoying to management or anyone else, who wants a short answer. The reason I sometimes give long answers is that the answer is not simple, or I need the question defined better in order to give a simple answer. I just can’t bear the idea to give an incorrect answer. I can’t bear to give a short answer to management then have someone come back and say well what about “this”, and management to come back at me and say well what about “this.” I work in complicated subjects. Very often the problems, the solutions, the questions, and the answers are all complicated. The problem with the media sometimes is they try to make a complicated subject simple and sometimes fail miserably. Sometimes they just have no clue what they are talking about and seem to refuse to want expert advice. I respect journalists who can take complicated science subjects and explain them simply. There is a difference between explaining something simply and accurately and explaining something simply and wrong. Asbestos coming out of a smokestack is simple. It is also wrong.